A new report released by the Campaign for College Opportunity shows that half of the more than 60,000 students who obtained an associate’s degree in California during the 2012-2013 school year took over four years to get their degree. This is an alarmingly long time, especially compared to the 4.7 years it takes the average student to complete a bachelor’s degree at California State University.

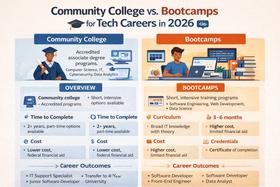

Many community college students choose to take that route because of the affordability. According to data from the College Board, in 2011, community college students paid an average of $2,713 in tuition and fees, compared to $7,605 for students who attended an in-state four-year institution. At less than half the cost, community colleges pose significant financial benefits for students on a tight budget.

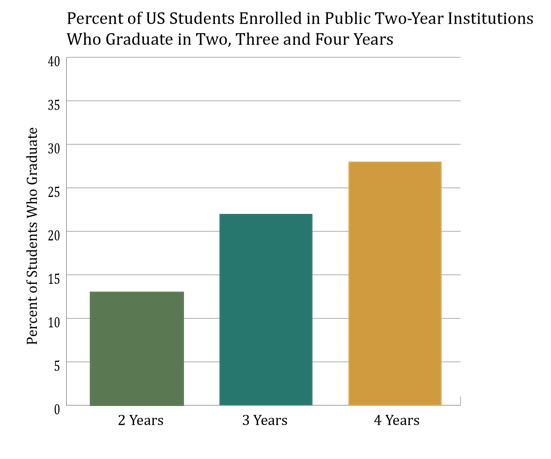

However, time seems to be the biggest enemy of students who begin post-secondary education at the community college level. The College Board’s report shows that of the cohort of students who started their community college studies in 2005, only 21 percent graduated within three years – a full year longer than is traditionally required. Many of the financial benefits gained by attending a two-year institution are lost if students aren’t able to complete their degree on time. Yet, students who enroll in a two-year program are the ones who are most likely to be impacted by factors that extend their graduation timeline. These factors are varied and many.

Insufficient Course Offerings

A few years ago, California’s massive budget crisis made it difficult for community colleges in the state to sustain the number of course offerings and staff needed to keep students on track to graduate in two years. As a result, fewer course sections were offered, teaching faculty were let go, and students found that classes they needed to take were full or had long waiting lists for admittance. To top it all off, students who couldn’t get into the classes they required instead had to take unnecessary courses to remain eligible for financial aid. For those students, waiting to take required courses while paying for ones that didn’t apply for their degree was a double-edged sword. Consequently, many California community college students who graduated in 2012-2013 did so with nearly 80 credits – or one-third more than is required for most two-year degrees.

Work and Family Obligations

A lot of today’s college students work at least part-time, and many work multiple part-time jobs or full-time jobs. Some do it out of necessity to pay for college, while others support their families while attending college at the same time. These students have a far more difficult time graduating in a reasonable timeframe because scheduling classes around these external obligations is difficult. A required course only offered in the mornings or every other semester may conflict with a student’s work schedule, childcare, or transportation needs. Unable to take their child to class or pay for school without their job, students instead wait and wait for their needed classes to be offered at a time they can take them. This alone can add months to a student’s graduation timeline.

Work and family obligations also serve to isolate students from the college experience. Rather than delving into the campus social scene or enjoying athletic events and other activities, these students may feel disengaged. The more detached a student is, the more likely they will miss class or drop out of college altogether. But the reality for many college-goers, especially those with low socioeconomic status, is that work and family come first, and improving oneself comes second.

Remedial Coursework

Studies show that anywhere from 28 to 40 percent of college students must take at least one remedial course. However, on average, students who need to brush up on basic skills need far more than just one course. Many students take an additional 20 credit hours in order to be ready for college-level learning, which are hours that do not apply toward one’s degree. That’s equivalent to an added semester and a half of tuition, fees, books, and other college-related expenses without actually doing any college-level work. All told, the remediation needs of students nationwide incur expenses in the neighborhood of $2.3 billion each year.

The need for remediation is especially strong amongst non-traditional students who have come back to school after a long hiatus. However, there is also a high need for college prep courses amongst low-income and minority students. Over 40 percent of African-American and Latino students must take a remedial course, as compared to 31 percent of white students. This need for remediation is also present among high schoolers preparing for college. Only 25 percent of students who took the ACT test in 2012 achieved a college-ready score in all four subject areas..png)

This represents a significant gap between what students learn in high school and what is expected of them in college. But community college admissions policies don’t help the situation either. Many community colleges require just a high school diploma for admittance; some don’t even need that. The result is that students are enrolling in community college without being prepared to undertake college-level work.

Being unprepared for the academic rigors of college study does not bode well for graduation and completion of a degree. Remedial students are more likely to drop out of college, and those who stay are less likely to complete their degree requirements than their peers. Moreover, only 25 percent of students who take remedial courses at a community college earn their certificate or degree. Thus, students who go to college to improve themselves leave because the time required to become college-ready is more than they can afford.

Lost Credits

Many students begin their studies at a community college with the intent of transferring to a four-year institution to complete their degree. Over 80 percent of community college students report that a bachelor’s degree is their ultimate goal. Still others begin their studies at a two-year institution and transfer to another two-year institution. But for many community college students, it not only takes longer to get their two-year degree, but some have the unfortunate experience of losing credits they’ve already earned when they transfer to another college, mainly if that institution is out-of-state.

This is not just a problem for California students. Research from the Graduate Center of the City University of New York shows that nationwide, 14 percent of community college students lose nearly all of their credits when transferring to a four-year college or university, and another 28 percent lose between 10 and 89 percent of the credits they’ve already earned at the community college level. Students lucky enough to have most of their credits transfer are more than twice as likely to get their bachelor’s degree, and 60 percent of them do so within four years of transferring. Yet, this is still somewhat discouraging news. Many of the students who successfully graduate with a bachelor’s degree do so after an extended period of time – four years for their associate’s degree and another four years to finish off their remaining undergraduate requirements. Eight years to earn a bachelor’s degree is expensive no matter which way one looks at it.

Changes Being Made

While many factors that prevent students from getting their two-year degree on time are out of the hands of community colleges, schools are nevertheless implementing changes to address some of the issues under their control. After budget cuts and revenue shortfalls of over $1 billion forced California community colleges to slash course offerings and teaching positions during the Great Recession, many schools are again in a position to add classes back to their schedules. More classes mean more available seats and more students getting into the courses they need to graduate quickly. Schools are also implementing student service programs that help students devise an academic plan beforehand to understand degree requirements and course sequences before enrolling in their first class. Campus counselors are also encouraging students to enroll full-time, if at all possible, to expedite the completion of their degree requirements and save money.

Community colleges and universities in California are also working to streamline the transfer process. The University of California system has implemented a vigorous marketing campaign at California’s community colleges to inform students about application procedures, financial aid opportunities, and academic planning tools. Additionally, the University seeks to align its pre-major pathways with existing associate’s degree programs so students who begin their studies at a California community college can seamlessly transfer their credits to an existing degree program at one of the University’s nine undergraduate degree-granting institutions. On-campus peer-to-peer mentoring programs at community colleges will also help students navigate the process of transferring to a four-year program.

Simplifying the transfer process between two-year institutions and the California State University system began in 2010, when then-governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed the Student Transfer Achievement Reform Act into law. The bill established a simplified process for community college students to transfer to the California State University system by creating two transfer-specific degrees – an associate of arts and an associate of science. Students who complete these degrees at a California community college are guaranteed admission to one of the member schools of California State University and are admitted as a junior. For the 50,000 students who transfer into the CSU system each year from one of the state’s community colleges, this is a welcome change.

Many community colleges are also implementing programs to reform the way that remedial classes are delivered. Some schools offer fast-track courses that reduce the time in class by half. Other schools have had success with learning communities, in which small groups of students take all their classes together, study together, and lend one another support. Still, other colleges have increased access to and the number of on-campus tutoring and mentoring programs, so students who just missed out on testing into college-level courses can still enroll, but with added academic resources at their disposal. These changes will help students complete their studies faster, reducing their costs. It will also reduce community colleges' expenses to bring their students up to college-level proficiency.

The extended stay that many students have at California community colleges negatively impacts their lives in the short and long term. The initial money they save by starting at a two-year school is negated by the additional years they spend getting their degree. The costs for an additional year of school add up to $7,600 for tuition, fees, books, and other related expenses. The extra time students spend in school also directly impacts the amount of money they make over the course of their lifetime. A student who takes four years to complete their associate’s degree stands to lose $30,000 in potential wages. According to data from the Campaign for College Opportunity, Los Angeles-area community college students who take six years to obtain their associate’s degree incur an additional $120,000 in expenses and lost wages over the course of their working lives.

Although California’s community colleges and universities have made positive strides toward helping students graduate on time, much work is left to do. High school students need to be better prepared for college-level work. Community colleges need to provide better academic planning services and learning support programs for remedial students. Universities need to continue to simplify the transfer process so students who work hard to complete their community college classes aren’t left with a transcript full of unusable credits. Doing so will garner benefits for students and institutions of higher learning, but as we’ve seen, the process is more straightforward said than done.

Questions? contact us on Facebook. @communitycollegereview